Now that the bogs are flooded for the winter, we have started our next big project at Pine Island Cranberry: sanding. Sanding is a fundamental component of our Pine Island Integrated Crop Management (PIICM) program, helping us manage the relationship between water, soil, weather, disease, insects, weeds, and nutrition.

Sanding is a process where we apply 1/2″ to 1″ of sand on the bog surface every five years on a rotating basis. This year we are scheduled to sand 232 acres. This procedure helps improve growth and yield by stimulating the development of new uprights (covering the base of the roots strengthens the root system and creates a more healthy vine) while also suppressing disease and reducing insects (by burying weed seed, spores, and insect eggs). It also improves soil drainage while at the same time absorbing and releasing heat so that frost danger in spring is lessened. This increases our efficiency by lowering the need for extra plant nutrition as well as saving water by cutting down frost irrigation times.

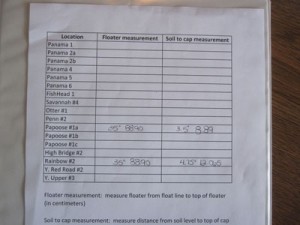

In New Jersey, it doesn’t always get cold enough for ice sanding (the preferred method for growers at more northern latitudes), so our team usually works with a sanding barge. This process starts as you might expect: checking on water levels. Our team needs to make sure the water is the right depth, so that Jorge Morales, our barge operator, doesn’t get stuck on any vines or worse, tear them out. “This weekend, the water levels dropped a little bit,” sanding team member Matt Giberson says. “We ended up having to let some water in.”

When barge sanding, it is particularly important to check for debris. The sand needs to be as pure as possible in order to prevent soil compaction (which can restrict water and limit growth) so we screen our sand before using it on the barge to take out any clay, stones, or other debris which could cause problems.

Our team begins to prep a couple of days beforehand by checking to see how much the water level needs to come up. The day before the crew arrives, a supervisor will get the water to sanding level (high enough to cover all vines) and measure out the distance the sander will travel. The crew will begin to sand on the deepest side. The water level can then be adjusted if necessary, which helps with dam conservation.

Our team also prepares by sending the necessary equipment out to the sanding location. A tractor with a winch is on one side of the bog, ready to move the length of the bog; an excavator is on the opposite side of the bog. The cable from the winch is stretched across the bog, through the sander (which has been lifted and put in the bog next to the excavator), and connected to the excavator.

On Wednesday, the sanding team was out at Harrison. “This one’s a little easier to do because it’s pretty square,” Matt says. “Oddly shaped bogs can be tough. But here Jorge just has to work his way to the middle and back and keep marking with stakes. It’s a simpler pattern.”

Harrison should also respond well to the sanding process. “Some varieties do better with sanding than others,” says PIICM manager Cristina Tassone. “With a Stevens bog our preliminary analysis shows that production can go down slightly, but Harrison is a Ben Lear bog, and Ben Lear seems to respond very well to sanding. So we’re experimenting a little with that.” Our PIICM program is also experimenting with how sanding affects the growth and spread of fairy ring, a fungus which works to kill cranberry vines in the root system. “Our suspicion is that it helps to spread the disease,” Cristina says, “so we’re skipping some bogs in the rotation where fairy ring has appeared. We’ll see what happens.”

The process itself is simple: a dump truck is loaded with two or three loader buckets of sand.

The dump truck then heads over to the bog being sanded, backs up to the excavator, and drops the load. The excavator operator then loads the hopper of the sander, while the sander operator moves along the cable, adjusting the opening for the sand to fall. Jorge is sanding at 1″ for this particular bog. The process is repeated, with the excavator and tractor moving forward the length of the bog together.

“It’s especially important to clean out the machines every night in case the temperature drops below freezing,” Matt says. “We clean out the sander, the trucks, the dams…everything. It’s all about efficiency.”