Harvest is going at full speed and all of our teams are doing whatever it takes to bring in this year’s crop. Matt Giberson, our new Blue Team supervisor, was out at Bull Coo on the home farm with his crew this week. Matt has been with us for a year and a half now, learning all the challenges and triumphs of growing cranberries and is applying knowledge of the water from winter flooding to the management of the harvest water flow.

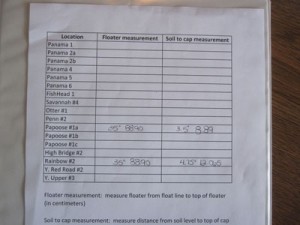

“My main job is to handle the water,” Matt says. “I was really nervous about it at first, especially with the reservoirs being so low. But I’m learning how it all works; I spend a lot of time talking to Bill and Fred, because they know more about the water than anyone else here. And I touch base every morning about our targets: what to pick, what to gather.” Matt is also getting used to the early mornings! “It’s a long drive out to Sim Place, and when you go to bed, you’re always worried about the water: did you close that gate? Is enough coming through?” With the reservoirs being so low, Matt also has to keep an eye on the Crisafulli pumps. “There was a clog at the gate at Red Road this morning; I could tell the stream wasn’t what it was supposed to be. Bill always says, ‘Be creative, have a Plan B’, so we brought some water down from the top. It finally cleaned itself out, and now we have plenty to finish this section.”

It helps to have a couple of experienced crew leaders. Joel DeJesus, who runs the picking crew, and Kelvin Colon, who runs the gathering crew, know what they need to do to keep the balance. “Communication is key, always,” says Matt. “If that goes well, everyone’s job is made a lot easier.” And everyone pitches in. Matt tries to keep Joel’s crew knocking berries at all times, and if Kelvin’s gathering crew catches up, they will help with other tasks, such as pulling sprinklers ahead of the picking crew, while waiting. As with everything else in agriculture, a lot depends on the weather. The wind was favoring the gathering crew, which helps speed up the process considerably. And they have specialized knowledge which also helps with efficiency: Joel keeps a set of tools on him at all times, so if the chain on a harvester breaks, he can usually fix it himself and save the equipment team a trip.

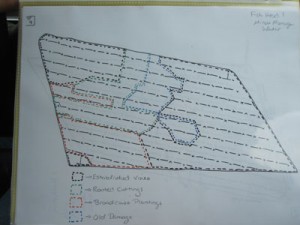

With water management so central to the operation, Matt believes that knowledge is power. “The more people know about the process, the better it is. They ask questions, you give them answers. Then they can see themselves if something’s not right. Vincent was out at Sim Place the other day and noticed a couple of boards had come out, and we were able to get that under control right away.” In turn, he asks plenty of questions and learns extensively from the team members that have been here for many years. Experienced team members such as Wilfredo Pagan, Ivan Burgos, and Jorge Morales, among many others, explained picking patterns to him. Each bog is picked in a specific pattern according to terrain, and the picking crew has to carefully move their harvesters around stakes which have been arranged by the team leader for maximum operational efficiency. Following this pattern allows for minimal damage to the vines. “That one’s still tough,” he says. “But it comes down to knowing your bogs, to keeping your feet in them and picking up the details. The more I walk them, the more I learn.”

Pine Island Cranberry is very happy to have Matt as the new Blue Team supervisor this harvest; he is a great example of the type of leadership we are trying to attract. He is passionate about farming, wants to know everything about how to grow cranberries, and is willing to do whatever it takes to help us achieve our mission. Most of our training on the farm is informal and on-the-job experience. This season, Matt has been able to lead his team and learn from the veterans at the same time, helping us do everything we do better every day.